Sportswriter Gordon Beard was among several who spoke at a luncheon honouring Hall of Fame third baseman Brooks Robinson following his retirement in 1977. “In New York, they named a candy bar [The Reggie Bar] after Reggie Jackson,” Beard said. We name our children after Brooks Robinson in Baltimore.”

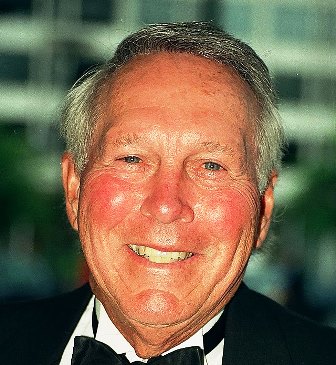

Indeed. Brooks Robinson is the most popular sports person in Baltimore history, quite a legacy considering the city has also produced Johnny Unitas, Cal Ripken, and Jim Palmer, among many other giants. That legend lives on because Robinson isn’t only the best fielding third baseman in baseball history; he’s also the nicest guy I’ve encountered in 45 years of covering the game.

“I’ve never known anyone in any profession more adored than Brooks,” stated former colleague Frank Robinson. “We’d go on road trips, and he’d stop on the side of the road to talk to complete strangers.” It’s incredible that he was such a superb player and so pleasant to everyone he encountered.”

Throughout his 23-year career, he was a force on the pitch. He was the position player with the most Gold Gloves, with 16. He was named American League Most Valuable Player in 1964 after hitting.317 with a league-leading 118 RBIs. He also placed in the top four in MVP voting four more times. He was named to 18 All-Star teams. He had a total of 2,848 hits. He is regarded as one of the finest clutch hitters of all time, having driven in the game-winning run in ten different games. He was also very durable, leading the AL in games played four years in a row, with at least 161 games played in each.

His defence was out of this world. He used to take ground balls on his knees and practise taking balls off his chest before games. His body was never rushed; he was always relaxed, which is essential for a third baseman. He had good feet in part because he began his professional career as a second baseman, only transferring to third base after reaching the main leagues in 1955. Then he played 2,870 games at third base, the most in baseball history. Robinson had wonderful, soft hands. He could use both hands. With his left hand, he ate and wrote.

“The first time I ever met Brooks was in my first spring training [1965],” former Orioles second baseman Davey Johnson said. “I saw he ate and wrote with his left hand. ‘My God, the best defensive third baseman does that,’ I thought. So for a year, I ate and wrote with my left hand. It didn’t help me at all. But I had to give it a go.”

Brooks was the master of the bunt play; his barehanded grab and throw across his body was flawless. Robin Roberts, a future Hall of Fame pitcher, joined the Orioles in 1962. On a bunt down the third base line in one of Roberts’ early starts, he cut in front of Robinson but didn’t make the play. At first base, the runner was safe.

“I patted him on the butt,” Robinson laughed many years later. “I told him, ‘Next time, give me that ball.’” ‘I’m OK with that play.’”

Robinson’s defensive prowess was on display during the 1970 World Series against the Reds. He made at least a half-dozen incredible plays. The Orioles won five games in a row.

As a result, he was dubbed “The Human Vacuum Cleaner.”

“I’ve never seen anything like what he did to us in that Series,” stated Reds manager Sparky Anderson. “He killed us.”

“God sent Brooks Robinson to play third base in the 1970 Series,” Reds manager Pete Rose stated. He got everything but a cold.”

“I made Brooks the MVP of that World Series,” Johnny Bench, the National League MVP that year, stated. “I fired 14 rockets at him, and he caught every single one.” I met him again during the 1971 All-Star Game in Detroit. I hit a BB at him in my second at-bat, and he simply picked it up like it was nothing. As I sprinted to first base, I flung my hands in the air. I fixed my gaze on him. He just laughed.”

Brooks Robinson was the first person I met in 1979. I was 22 years old and working for The Washington Star on a pair of Orioles pieces. He worked as a broadcaster for the team. He told me, with that endearing Arkansas accent, “If you ever need anything, please let me know.” I covered the club for the following two seasons before becoming the Orioles beat writer for The Baltimore Sun from 1986 through 1989. Brooks Robinson and I spent a lot of time together. We’re not meant to get too close to the players, present or past, as reporters. That was impossible with Brooks.

He was that amazing, kind, compassionate, and giving. Robinson attended the Orioles’ fantasy camp for decades, playing until his late 60s. The campers had a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to play alongside Brooks Robinson.

“How did you do at fantasy camp?” I once inquired of him.

“I was great,” he said and laughed. “You should have seen me.”

When a couple of business endeavours failed, he fell into financial difficulty, and the fans of Baltimore helped bail him out. They knew that’s what he’d have done, what he excelled at: helping others. He spent the most of his career with BAT, the Baseball Assistance Team, which assisted former players in need of assistance of any type. The Orioles marked the 45th anniversary of Robinson’s retirement with a “Thanks, Brooks” day at Camden Yards a year and two days ago, complete with an appearance by Robinson before the game. They also gave out a large number of tickets to the Baltimore Boys & Girls Club.

Our family travelled to Florida in January. We went to an aquarium one day. We spent the most of the day there, where I met baseball enthusiasts from all across the nation and chatted with hundreds of individuals. Three of them told me they named their kid Brooks Robinson.

More in Sports: https://buzzing.today/sports/

Photo Credits: https://commons.wikimedia.org/